Elon Musk, co-founder and chief executive officer of Tesla Motors.

Yuriko Nakao | Bloomberg | Getty Images

In October 2016, Tesla CEO Elon Musk made a bold promise: One of the company’s vehicle’s would drive itself from Los Angeles to New York by the end of 2017 in what he dubbed a demonstration of “full autonomy.”

The trip, which received international attention, was announced in conjunction with Tesla disclosing all of its vehicles were being equipped with “full self-driving hardware” that would “be substantially safer than a human driver.” The company had previously spent a year testing the new hardware.

But the trip never happened and now – more than three years later – Tesla’s vehicles with its Autopilot driver-assist system still require driver monitoring. The system has also been criticized for allowing for driver misuse and its role questioned in at least three fatal crashes.

In the past decade, there has been no shortage of optimism from automakers and companies like Uber and Lyft over emerging technologies in transportation – and in the case of Tesla, unmet goals. But after years of hype, automakers and tech companies in the space will look to deliver on ambitious promises around both autonomous and electric vehicles in the 2020s.

Autonomous vehicles have yet to hit the road beyond test phases and limited pilot programs while electric vehicles are commercially available but not yet widely adopted.

The companies see both segments as multitrillion-dollar business opportunities. They’ve also touted the technologies as ones that will create a safer, more environmentally friendly way of transportation. That has led Tesla, General Motors and others to announce plans for a future with significantly lower, even zero, auto accidents and vehicles with zero emissions.

Companies in the next decade are expected to invest more in the two technologies. A report by AlixPartners earlier this year estimated the industry’s spending on autonomous driving and electric vehicles will reach a cumulative $85 billion by 2025 and $225 billion by 2023, respectively.

Industry experts expect all-electric vehicles to enter the mainstream before autonomous vehicles due to regulatory concerns, cost and other factors, but even in that category, progress has been slow moving.

Autonomous goals

Creating and launching driverless vehicles has been easier said than done. There are major safety and regulatory barriers as well as unforeseen technological hurdles.

Much of the wind was taken out of the sails for a rapid proliferation of autonomous vehicles in 2018, when an Uber self-driving test vehicle was involved in a fatal accident involving a pedestrian.

“The Uber fatality was really the thing that kicked it off,” said Sam Abuelsamid, principal research analyst at Navigant and an engineer, referring to the slowing of the “accelerated hype curve” around autonomous vehicles.

The death of the pedestrian, Elaine Herzberg, was the first known fatal accident involving an autonomous vehicle, two years after Uber launched its first self-driving test vehicles on U.S. roadways.

As a result of the accident, Uber ceased testing for months and autonomous vehicles as a whole were put under heavy scrutiny that continues to have a ripple effect on the industry. The company earlier this year said it is planning a limited launch of its newest self-driving vehicle with additional fail-safes and no human drivers in 2020.

“People are actually taking this problem more seriously,” said Abuelsamid, adding many of the main players have acknowledged how challenging autonomous vehicles can be and have sought multibillion partnerships to ensure they’re done right.

For instance, Ford CEO Jim Hackett said at a Detroit Economic Club event in April, “We overestimated the arrival of autonomous vehicles.”

Meanwhile, GM in January 2018 said it planned to deploy autonomous vehicles at scale in 2019, but the company delayed its launch last July, saying that more testing was needed. GM is expected to deploy an autonomous ride-hailing fleet as early as next year in San Francisco.

Other companies have announced targets in the early part of the next decade. Ford expects a commercial self-driving vehicle business by 2021; and Hyundai Motor with auto supplier Aptiv created a $4 billion joint venture that aims aiming to launch autonomous vehicles in 2022.

An Argo-modified Ford autonomous vehicle parked in Manhattan on Friday, July 12, 2019.

Paul Eisenstein | CNBC

Tesla’s new goal for autonomous vehicles is 2020. Musk earlier this year said the automaker expects to have 1 million robotaxis on the roads next year. He also predicted that within two years Tesla will be making cars with no steering wheels or pedals — something current safety regulations do not allow.

Volkswagen, Volvo and others have discussed plans for autonomous vehicles or services but have not given exact details on timing.

Lyft, which currently offers autonomous vehicles in Arizona through a partnership with Alphabet’s Waymo, has assigned around 400 of its engineers to work on two distinct self-driving initiatives, including a ride-hailing platform and the development of a “self-driving stack,” also known as the brains of the car, instead of an entire vehicle.

“There’s every reason to launch this cautiously and carefully,” said Stephanie Brinley, principal automotive analyst at IHS Markit. “You’ve really got to be as safe as you possibly can. I think automakers should be able to pull it back a bit if they have to. There have been delays, but there has been forward progress.”

Waymo has been the most successful in launching autonomous vehicles. It has operated a limited ride-hailing fleet with the vehicles in metropolitan Phoenix since December 2018.

‘Moonshot targets’ on electric vehicles

Nearly every major automaker in the past decade also has promised a fleet of all-electric or “electrified” vehicle offerings in the 2020s.

GM, Volkswagen, Nissan and others have announced plans to sell 1 million all-electric vehicles or more globally a year during the 2020s. Others such as Toyota have announced similar goals for “electrified vehicles,” which include plug-in hybrid models in addition to all-electric.

Both GM and Volkswagen previously missed sales targets regarding electric vehicles. In 2012, GM said it planned to have 500,000 electrified cars on the road by 2017 (it ended up with 243,133). In 2010, Volkswagen said it expected to sell 300,000 electrified vehicles annually by 2018 (its total last year was closer to 100,000).

The hype around all-electric vehicles was so high a decade ago that J.D. Power and Associates predicted that by 2020, global hybrid and EV annual sales would top 5 million units. It has since lowered those expectations to 4.4 million vehicles, up from an expected 2.6 million in 2019.

Many other analysts and forecast firms expect acceptance of all-electric to begin in the 2020s but remain far from mainstream. Lack of charging infrastructure, lower-than-expected gas prices and battery costs all contribute to the lackluster sales of all-electric vehicles.

In January, GM previewed a crossover that is expected to be Cadillac’s first all-electric vehicle on the company’ next-generation all-electric vehicle architecture.

GM

“There’s a lot happening and I think we have realized some of those early projections were more moonshot targets,” Brinley said. “Of course, you set an ambitious goal because if you don’t set a goal, you won’t get there at all.”

IHS Automotive forecasts sales in the U.S. will represent 3% of total domestic sales in 2020, followed by 8% in 2025 and 11% in 2030. The auto research and intelligence firm expects 120 EV models to be offered in the U.S. by 2025.

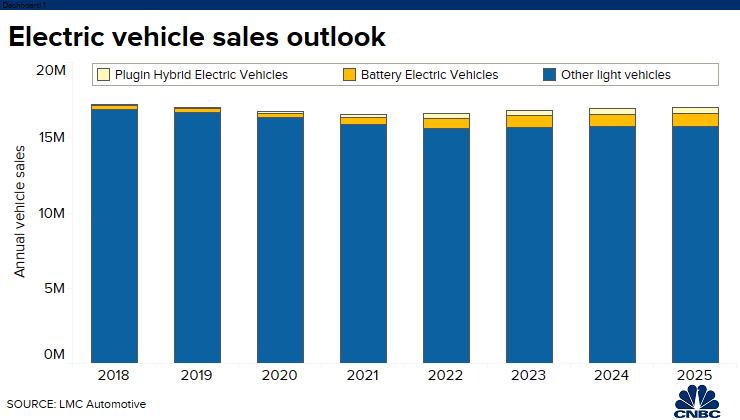

Others such as LMC Automotive are slightly less optimistic about the growth of EVs in the 2020s. The company expects electric vehicle sales to steadily increase to only 5.1% of the U.S. market by 2025.

“It’s been promised. We’ve been talking about it forever. For EVs, we’re at a tipping point at least for availability,” said Jeff Schuster, president of global forecasting at LMC Automotive. “The last 10 years were probably filled with a bit of overpromise and underdeliver.”