Speaking of ways, pet, there is such a thing as a tesseract.

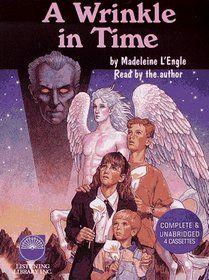

I had eye surgery at the very end of third grade. I knew that I wouldn’t be able to swim for six weeks of summer vacation, I had to wear this really fetching sunglasses-visor combo whenever I went outside, and, worst of all, my reading time would be severely limited. Luckily, a friend of my grandmother’s thought to bring me the four-tape audiobook version of A Wrinkle in Time. L’Engle herself read the audiobook, and to this day, part of me actually does feel like she really it read to me when I wasn’t supposed to be reading to myself. I immediately saw myself in Meg Murray, who also wore glasses (though my eye surgery meant that I wouldn’t have to wear mine again until I was a senior in high school), and who felt set apart from her peers.

L’Engle’s writing made me feel like I was smart enough to understand adult mathematical concepts (like the tesseract), but it was simply that she was good at explaining these concepts to children; in Walking on Water, she wrote, “there is no idea that is too difficult for children as long as it underlies a good story and quality writing.”

I slowly made my way through the rest of the Time Quintet, since it was harder to source some of the later books in the late 1990s. I didn’t give much thought to L’Engle herself until I saw that she’d died, early on in my first year of college.

Madeleine L’Engle Camp was born in 1918. She was the only child of parents who had been married for some time and had different ideas as to how to raise their daughter — this comes up a few times in the biography Becoming Madeleine, which was written by her granddaughters. One parent insisted that she attend boarding schools, including one in Switzerland where she was dropped off after thinking she would be spending the day with her parents. There, she was a middling student. She went on to attend Smith College. After college, she moved to New York City and was, for a time, an actress and playwright. Her first book was published when she was in her late twenties.

Despite early success in publishing, her career stalled out a bit in her thirties, when she was parenting young children. She wrote in A Circle of Quiet, the first of her published journals, that she considered giving up writing at 40. A Wrinkle in Time was published in 1962, when she was 44 years old. In her life, she would publish more than 50 books, including poetry, novels for young readers, adult novels, picture books, books on religion, and poetry.

L’Engle married the actor Hugh Franklin in 1946. They eventually purchased a farm, Crosswicks, and ran a general store while their children were young. Later on, Franklin went back to work in the theater — and eventually scored a long-running part on the soap opera All My Children. In later, life L’Engle traveled and gave lectures. She was also the volunteer librarian at the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine in New York City.

L’Engle’s major works for younger readers are broken up into chronos: what she calls “wristwatch time,” her books about the Austin family — and kairos: more subjective, qualitative time, as in the books about the Murrays. There is some overlap between characters in all of her work: characters who were teenagers in the books she wrote as a young woman appear as matriarchs later on, an Austin sibling pops up in an unrelated story. L’Engle’s characters continued to be alive to her, and why shouldn’t they go on visits? A notable exception is Charles Wallace Murray, who is never seen again after Many Waters, but it is implied that the reason is top secret (potentially even to L’Engle herself).

The Crosswicks Journals are almost a thousand pages of L’Engle talking about writing, life, parenthood, and religion. (You can buy the four parts in paperback, but there’s also a very reasonably priced Kindle omnibus if you don’t plan to take notes, which, if you couldn’t tell, is my current project.) She was a practicing Anglican, a Christian universalist who believed, as she wrote in A Stone for a Pillow, that, “All will be redeemed in God’s fullness of time, all, not just the small portion of the population who have been given the grace to know and accept Christ.” In response to this, many Christian bookstores refused to stock her work. A Wrinkle in Time was frequently challenged because of its blend of religion, supernatural concepts, and science.

I do not have much capacity for faith, but I have always had a lot of room in my life for awe, and that was something I found in A Wrinkle in Time as well as in the books that came after it. L’Engle believed in both the concept of god and science and that they were the same thing. When asked about science fiction by the New Yorker, she responded “Isn’t everything?”

Sometimes, even in her purported nonfiction, L’Engle abandoned literal truth for emotional truth. Her family has disputed some of what is in her journals (calling them “pure fiction” in the New Yorker), and her children were, occasionally, hurt by what she used as material in her novels. Her daughter Maria joined the family after losing both of her biological parents, and Meet the Austins features a family that welcomes a very difficult child whose biological parents had died. To L’Engle, it was clear that Maria was not Maddy and that that is what writers do. In the New Yorker interview, Maria called her “such a storyteller that she gets confused about what really happened.”

Madeline L’Engle died at the age of 88, in 2007. Her grandchildren have preserved her legacy and have brought to light some pieces from her back catalog. One of her granddaughters, Charlotte Jones Voiklis, runs L’Engle’s Twitter account, which has a way of tweeting “Stay angry, little Meg,” Mrs Whatsit whispered. “You will need all your anger now.” whenever something particularly devastating happens in U.S. politics. For me, it’s honestly one of the best arguments for staying on Twitter.

L’Engle’s family also runs writing retreats near Crosswicks. A short, illustrated book taken from a story about Charles Wallace attending elementary school in space, Intergalactic P.S. 3, was released in 2018 and is cute on its own, though it has a few crossover scenes with A Wind in the Door. L’Engle’s papers are now part of the Sophia Smith Collection at Smith College.

Her early novels, including Ilsa, And Both Were Young, and Camilla, have been rereleased, which means that I can finally get that copy of A Live Coal in the Sea I sought in the late 1990s. I had no idea what it was about, but the woman was truly a master of titles. A Severed Wasp? I don’t even care what it’s about. I’m in. L’Engle is one of the authors I go to time and time again when I want to feel like the world I live in has its own magic, and she has not disappointed me yet.