The Republic of Mauritius, located off the east coast of Africa, is full of Indians who speak French. The story of how it got that way is an intriguing one.

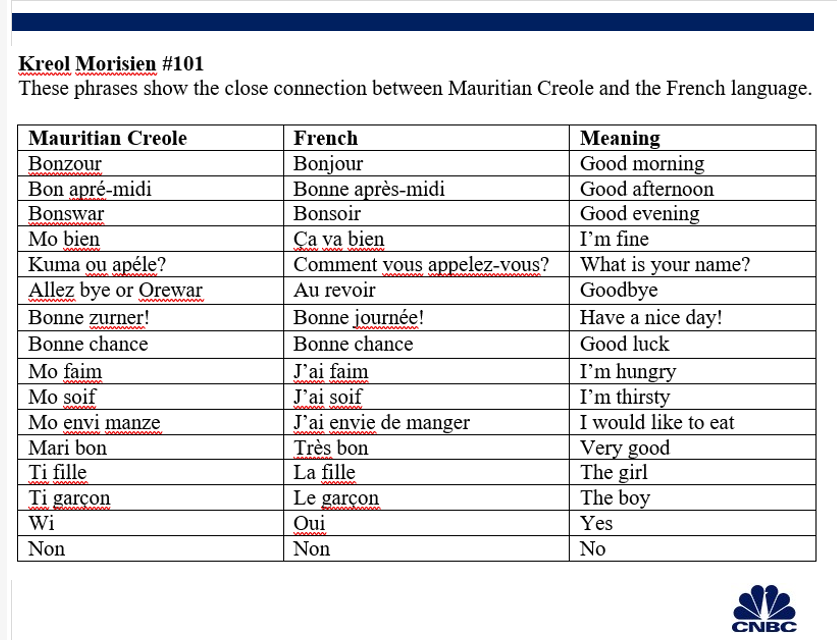

Visitors may be surprised at the predominance of French influence on this island state in the Indian Ocean — a destination best known for its powdery beaches, aquamarine lagoons and reefs teeming with marine life. That influence pervades not just the spoken language — be it French or Kreol Morisien, the local dialect — but also the island’s religion, law and architecture.

Aerial view of the Republic of Mauritius.

Norbert Figueroa / EyeEm | EyeEm | Getty Images

Spoken by 90% of the population, French is a vital element of Mauritian culture. English is the medium of instruction in schools, but French predominates in daily discourse and in the media. For example, just one or two of the 16 pages in the island’s mostly widely read newspaper, L’Express, are in English. Although English is spoken in Parliament, by law French is allowed there too.

How the Indo-Mauritians got here

There are more than 1.26 million people living in Mauritius, and Indo-Mauritians make up 75% of the population. Most of today’s Indo-Mauritians trace their lineage back to the Girmityas, indentured laborers who migrated to work on colonial British sugarcane plantations around the world. Between 1830 and 1924, half a million of them went to Mauritius alone.

Harvesting sugar cane in Mauritius.

santosha | E+ | Getty Images

Why Indo-Mauritians speak French

Like many former colonies, Mauritius experienced separate, distinct periods defined by who was in charge: Dutch control from 1664 to 1710, French rule from 1715 to 1796, and finally British rule from 1814 to independence in 1968. Given that the British ruled the island for such a long time, it would be reasonable to expect the English language to dominate.

Two reasons explain why it doesn’t: First, when France handed the country over to Britain, in terms dictated by the 1814 Treaty of Paris, the British agreed to respect the language and laws of the inhabitants. Second, Britain regarded the island as too small and insignificant for settlement, so very few English speakers ever settled there.

A traditional creole Sega dance at sunset in Ville Valio, Mauritius.

Dmitry_Chulov | iStock Editorial | Getty Images

Hotel manager Pierrot Barbe described himself as a true Mauritian. “I’m a real mix with my mother’s family having come from Tamil Nadu and my father from Madagascar.”

A polyglot like most of his fellow countrymen, he prefers to write in English and speak in French. But in informal settings, at home and with friends, most people speak Mauritian Creole.

Born during French rule among the majority slave population, the lingua franca remains an integral part of the islanders’ heritage and identity. It’s mainly French-based, said Barbe, although the meanings of some words have shifted. It contains some English words and borrows from African and Southeast Asian languages, too.

Religion and architecture

Around a third of Mauritians are Christians, with 80% of that group identifying as Roman Catholics. In 1723 during French rule, a law was passed that required all slaves brought to Mauritius be baptized Catholic. Later, French doctor and Catholic missionary Jacques Desiré Laval (1803-1864) was said to have converted over 67,000 people; he was beatified in 1979.

As a result, churches are ubiquitous. Two stunning Roman Catholic examples are Cap Malheureux’s much-photographed red-roofed Notre Dame Auxiliatrice Chapel in the north and Mahébourg’s Notre Dame des Anges in the southeast.

French colonial houses and public buildings also add lashings of architectural charm to the island. Well worth a visit is Château de Labourdonnais in the north, named for the first French governor, Mahé de Labourdonnais. He founded the capital, Port Louis, which boasts two fine examples: Government House and the 26-acre Line Barracks compound.

One of the island’s top attractions, Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam (SSR) Botanic Gardens at Pamplemousses, not far from Port Louis, was established by the Lyonnais missionary-turned-entrepreneur, horticulturist and botanist Pierre Poivre (1719-1786). Famous for its variety of tropical plants and its long pond of giant Amazonia lily pads, it is also home to the charming Château de Mon Plaisir.

Giant water lilies in Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam Botanical Garden, Mauritius.

Romeo Reidl | Moment | Getty Images

Another architectural jewel is Château des Aubineaux (1872). Located in the south, it is home to a museum dedicated to the history of tea-growing in Mauritius. The chateau proprietors own the flourishing Bois Chéri tea factory, where visitors can take a tour and then taste the renowned black vanilla tea.

What about French cuisine?

Except for the French gastronomy offered by the higher end of the island’s 150-plus hotels and resorts, there is little French influence on modern Mauritian cuisine.

Seafood predominates, as do Indian-style curries eaten with rice and breads, particularly the flatbread known as faratas.

An amalgam of laws

Though the British brought their own laws with them, elements of France’s Napoleonic Code still exist. One of these provides that all beaches are open to the public up to the high tide mark, so even the most elite coastal hotels share beach fronts with the public.

Seems those quintessentially French values — liberté, égalité and fraternité — are still alive in the Republic of Mauritius.